Freebie and the Bean

| Freebie and the Bean | |

|---|---|

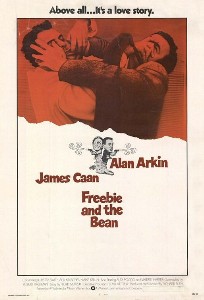

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Richard Rush |

| Screenplay by | Robert Kaufman |

| Story by | Floyd Mutrux |

| Produced by | Richard Rush |

| Starring | James Caan Alan Arkin Loretta Swit Jack Kruschen Mike Kellin Alex Rocco Valerie Harper |

| Cinematography | László Kovács |

| Edited by | Michael McLean Fredric Steinkamp |

| Music by | Dominic Frontiere |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 113 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3 million[1] |

| Box office | $12.5 million in the United States and Canada[2] |

Freebie and the Bean is a 1974 American buddy cop black comedy action film starring James Caan and Alan Arkin, and directed by Richard Rush. The film follows two police detectives who wreak havoc in San Francisco attempting to bring down an organized crime boss. The film, which had been originally scripted as a serious crime drama, morphed into what is now known as the "buddy-cop" genre due to the bantering, improvisational nature of the acting by Caan and Arkin. Reportedly, by the end of filming, both actors were confused by the purpose of the movie, not knowing that they had stumbled into a successful character formula. The film was popular enough to spawn various other successful film franchises such as, Lethal Weapon, 48 Hours and Beverly Hills Cop. Loretta Swit and Valerie Harper appeared in supporting roles.

Plot

[edit]Freebie and Bean are a pair of maverick detectives with the San Francisco Police Department Intelligence Squad. The volatile, gratuity-seeking Freebie is trying to get promoted to the vice squad to garner perks for his retirement while the neurotic and fastidious Bean has ambitions to make lieutenant. Against a backdrop of the Super Bowl weekend in San Francisco, the partners are trying to conclude a 14-month investigation, digging through garbage to gather evidence against well-connected racketeer Red Meyers, when they discover that a hit man from Detroit is after Meyers as well. After rejecting their pretext arrest of Meyers to protect him, the district attorney orders them to keep him alive until Monday.

After locating and shooting the primary hit man, and distracted by Bean's suspicions that his wife is having an affair with the landscaper, they continue their investigation seeking a key witness against Meyers who can explain and corroborate the evidence. In the midst of this, they foil a second hit on Meyers by a backup team, leading to a destructive vehicle and foot pursuit through the city, after which they learn that Meyers is planning to fly to Miami before Monday. Tailing him, they receive word that their witness has been located and a warrant issued for Meyers' arrest. Unknown to them, a woman Meyers picked up at a local park is a female impersonator looking to rob him.

During the arrest attempt at Candlestick Park, Bean is shot by the thief, who flees with Meyers into the stadium where the Super Bowl is underway. Freebie corners the thief in a women's restroom. Despite being shot himself, he rescues a hostage and kills the thief after he nearly bests Freebie with his unexpected martial arts skills. The D.A. arrives after the shootings and tells Freebie that the warrant is canceled because the witness was assassinated on the way to the station. Freebie goes nuts and demands to be allowed to arrest Meyers, which is granted by the lieutenant in command of his squad, only to find that Meyers has died of a heart attack. Freebie is further demoralized to learn that the evidence they gathered was planted by Meyers' wife in an extra-marital conspiracy with his lieutenant.

Bean is not dead after all, however, and in the ambulance the two wounded partners engage in a free-for-all when Freebie thinks Bean has been playing a joke on him, causing yet another accident.

Cast

[edit]- James Caan as Det. Sgt. Tim "Freebie" Walker

- Alan Arkin as Det. Sgt. Dan "Bean" Delgado

- Loretta Swit as Mildred Meyers

- Jack Kruschen as Red Meyers

- Alex Rocco as D.A. Walter W. Cruikshank

- Mike Kellin as Lt. Rosen

- Paul Koslo as Whitey

- Valerie Harper as Consuelo Delgado

- Linda Marsh as Barbara

- Christopher Morley as Transvestite

- Maurice Argent as Tailor

- Gary Kent as Ambulance Attendant

- Janice Karman as Teen

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]The film was based on an original script by Floyd Mutrux, who originally intended to produce his own property. In April 1972, he sold it to Warner Bros.[3]

Mutrux maintained he had gotten offers from other studios but elected to go to Warners because he felt studio vice president Richard Zanuck was "the straightest shooter I've ever known."[4]

The comedy followed on the heels of two popular action films about the San Francisco Police, Bullitt (1968) and Dirty Harry (1971), and incorporates plot elements prominent in both. James Caan later called the film "sort of The Odd Couple in a squad car, detectives, hopefully funny."[5]

Mutrux claims Al Pacino was offered one of the leads but his agent requested $250,000 plus a percentage of the profits, so Warners went with James Caan. This casting happened in June.[4] By August Richard Rush was attached to direct.[6]

Rush described the original script as about:

Two corrupt cops who ride around in a police car, quarreling with each other like an old married couple. You were never sure which one was the wife and which one was the husband. They became interchangeable. There was also the somewhat clumsy, rough skeleton of the plot concerning a criminal that they must keep alive to testify while assassins are contracted to kill him, which survived through our final film screenplay. I liked these ideas but there was nothing else there to make a movie work.[7]

Rush says John Calley, head of Warners, told the director he could turn it into a "Dick Rush picture...He was very generous and promised the studio would be very agreeable. It was the kind of offer that you can't refuse."[7]

Mutrux left the project and Rush rewrote the script with Robert Kaufman. The director says "we wrote a new screenplay about two bickering cops that became a prototype of the buddy cop movie. I put a lot of meat on the bones, with the unstereotypical wife of Freebie tormenting him with jealousy and the comic relief of their relationship."[7]

In October, Alan Arkin signed to costar with Caan.[8] Rush says Calley, who had worked with Arkin on Catch-22, warned the director that Arkin was "a director killer", but Rush insisted.[7]

Before filming, Rush worked on the script with the two stars and Kaufman in several improvisational sessions. Rush says "at my suggestion they turned what had originally been serious drama into bizarre comedy. Slowly their relationship took on the pains and pleasures of a friendship neither could live with or without."[9]

Arkin admits that it was Rush's idea to turn the film into a comedy. "I hadn't thought about it. I didn't see it in the script."[9]

Shooting

[edit]Filming took 11 weeks in 1973. It was a difficult shoot, in part because Arkin and Caan felt their characters were being made secondary to stunts and action sequences.[9]

Arkin said his relationship with Caan "was great. There is a very exciting interaction between us. Jimmy pushes me and forces me to change...But a lot of the time we've taken a back seat to the action."[9]

There were difficulties between Rush and Arkin/Caan. Rush says "the main factor was Arkin. Caan was a copycat. He was Arkin's buddy and would do anything Arkin did...Arkin needed conflict as part of his method, and it was horribly disruptive, but it didn't show in his work."[7]

Key scenes were shot on location in San Francisco at Candlestick Park. Dealing with local authorities reportedly was difficult for the crew.[9]

The plot includes the protagonists’ repeated "totaling" of a series of their own unmarked police vehicles during three different chase-crash sequences. One sequence was filmed on an elevated portion of the since-demolished Embarcadero Freeway, ending with their police vehicle car crashing into an apartment building. After the car lands in an elderly couple's bedroom as they are watching television, Arkin's character collapses from nervous shock against the wall as Caan's character calls for a tow truck, adding that their location is “on the third floor”. The couple retains their aplomb throughout.[10]

Rush said he "shot the film partly in a Tom and Jerry style, with lots of car chases and car crashes, and the heroes are being indestructible. The audience is laughing and enjoying themselves and suddenly Freebie would drive around the corner into a marching band of kids, and just sloughed through them. The audience thought Wait a minute. What am I laughing at?, and the style of the film had changed to stark realism. There was a lot of game-playing in the picture."[7]

"I never actually knew what Rush wanted," said Arkin at the end of filming. "He [Rush] is so uncertain it's hard to handle," said Caan.[9]

Release

[edit]Plans to distribute the film in early 1974 were shelved due to concerns about competition with Peter Hyams' similar Busting. The film opened the 1974 Chicago Film Festival.[11] Freebie and the Bean was issued as a Christmas release.

Home media

[edit]The film was released on DVD in 2009 through Warner Home Video's Warner Archive label.[12]

Reception and legacy

[edit]The film was panned by critics upon release. A.D. Murphy of Variety called it a "tasteless 'comedy' about two dumb cops breaking the law".[11]

Peter O'Toole agreed to be in The Stunt Man on the basis of Rush's work on Freebie and the Bean.[13]

The film was featured in the 1995 documentary film The Celluloid Closet.[14]

A 2018 article in Rolling Stone alleged that Stanley Kubrick called Freebie and the Bean the best film of 1974.[15]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 23% of 26 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 5.6/10. The website's consensus reads: "A sour blend of misguided comedy and all-out action,[when?] Freebie and the Bean is a buddy cop picture that's far less than arresting entertainment."[16]

Box office

[edit]The film became a substantial box office success.[10] Through early 1976 it had earned rentals of $12.5 million in the United States and Canada.[2][17] It was one of Caan's most successful movies after The Godfather.[18]

Television

[edit]A short-lived nine-episode television series based on the film and sharing its title, starring Tom Mason and Héctor Elizondo in the title roles, was broadcast on CBS on Saturday nights at 9:00 PM in December 1980 and January 1981.[19][20]

Accolades

[edit]Harper was nominated for the Golden Globe for New Star of the Year for playing the Hispanic wife of Alan Arkin.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "McElwaine Has 22 Readying; Finds Forgotten WB Coppola". Variety. November 12, 1975. p. 6. Retrieved June 27, 2022 – via Archive.org.

- ^ a b "All-time Film Rental Champs". Variety. January 7, 1976. p. 20.

- ^ MOVIE CALL SHEET: Rohmer Shooting in Paris Murphy, Mary. Los Angeles Times 7 Apr 1972: g20.

- ^ a b Another Joanna for Johnny Carson? Haber, Joyce. Los Angeles Times 22 June 1972: g19.

- ^ James Caan: Hollywood's Jock of All Trades, Haber, Joyce. Los Angeles Times 27 May 1973: o11

- ^ MOVIE CALL SHEET: Peck, Desi Jr. Set for 'Billy Two Hats', Murphy, Mary. Los Angeles Times 21 Aug 1972: f17.

- ^ a b c d e f Rowlands, Paul. "AN INTERVIEW WITH RICHARD RUSH (PART 3 OF 4)". Money Into Light. Archived from the original on 2019-08-29. Retrieved 2019-09-14.

- ^ MOVIE CALL SHEET: Trio Signed for New 'Love Bug' Escapade, Murphy, Mary. Los Angeles Times 25 Oct 1972: e11.

- ^ a b c d e f Murphy, Mary (3 June 1973). "Movies: They Almost Called the Cops on a Cops-and-Robbers Film". Los Angeles Times. p. q22.

- ^ a b Clement, Nick (17 September 2017). "Moviedrome Redux: 'Freebie And The Bean' (1974)". wearecult.rocks. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ a b Murphy, A.D. (November 13, 1974). "Film reviews: Freebie and the Bean". Variety. p. 36.

- ^ "Warner Archive Collection". Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-06-15.

- ^ Stunt that beat GoliathLucas, John. The Observer 4 Jan 1981: 30.

- ^ Sub-Cult 2.0 # 10 Freebie and the Bean (1974) — Nathan Rabin's Happy Place

- ^ Nick Wrigley Updated: 8 February 2018 (2018-02-08). "Stanley Kubrick, cinephile". BFI. Archived from the original on 2014-07-16. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Freebie and the Bean". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ FIRST ANNUAL 'GROSSES GLOSS', Byron, Stuart. Film Comment; New York Vol. 12, Iss. 2, (Mar/Apr 1976): 30-31.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (September 27, 2022). "The Stardom of James Caan". Filmink.

- ^ Richard Meyers (1981). A.S. Barnes (ed.). TV detectives. p. 276.

- ^ Vincent Terrace (1985). Encyclopedia of Television Series, Pilots and Specials: 1974-1984. VNR AG. p. 154.

- ^ "The Hollywood Foreign Press Association". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

External links

[edit]- 1974 films

- 1974 action comedy films

- 1970s action comedy-drama films

- 1974 black comedy films

- 1970s crime action films

- 1970s buddy comedy-drama films

- 1970s crime comedy-drama films

- 1970s buddy cop films

- 1970s police comedy films

- American action comedy-drama films

- American buddy comedy-drama films

- American crime action films

- American buddy cop films

- American crime comedy-drama films

- 1970s English-language films

- Fictional portrayals of the San Francisco Police Department

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films directed by Richard Rush

- Films scored by Dominic Frontiere

- Films set in San Francisco

- Films set in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Films shot in San Francisco

- American police detective films

- Warner Bros. films

- 1970s American films

- English-language crime action films

- English-language crime comedy-drama films

- English-language black comedy films

- English-language action comedy-drama films

- English-language buddy comedy-drama films

- English-language thriller films